You have probably heard some respectable sailor or coach say "never ever sail in dirty air," or to

"always tack out immediately," but while that is a great guideline the absoluteness of these statements are misleading. There is a common picture that I would like to paint of a big fleet. Let's say you are sadly not bow out,

or that you are in second row in a crowd of starboard tack boats coming off the line

who are all in dirty air and who are all going to the correct (in this case left) side of

the course. The first move for me is not to tack, it is to quickly read the body

language of the person or people who are giving me the worst dirty air.

If they are antsy, squirming looking over their shoulders again and

again, you might hold on in their dirty air because they are about to tack

out and give you clean air.

On the other hand if the boat giving you the worst dirty air is settling in,

hiking hard and focused you will probably have to tack out or foot off to get out of there. But before you do this, look at the body language of the boat that is pinning you or the boat that you will have to duck if you tack onto port. If they

look like they are about to tack then wait for them to tack and

then tack with them. If you tack with them, not only have you avoided

having to duck them, they can now act as a buffer boat for you. If someone

calls starboard on them they will have to call to you for room to tack early enough for you to be able to tack. They will probably lee-bow the

starboard tacker and even if they don't you might be able to lee-bow them,

and there is a chance that in this position you will get the original starboard tacker's, or your

buffer boat's starboard tack lane (remember that we are assuming that

the left is the correct side of the course so getting onto starboard in this way is good). On

the other hand if your buffer boat decides to duck the starboard tacker, you

are within your rights to call for room to duck, and if you can get a good

rounding of the starboard tacker's transom* you end up on the same ladder rung

as your buffer boat just like in a rabbit start. Then you can tack back

onto the favored tack as soon as there is a lane to tack into and you get

first pick of lane because you are pinning your buffer boat.

Going back to

the situation of being stuck in a crowd of starboard boats in dirty air

all going the same (favored) way, if both the boat upwind is not going to tack away and the boat to windward pinning you is not

about to tack and act as a buffer boat for you, then you need to crane your

head and look to windward and astern of this windward boat to look hard at exactly

which boats you would have to duck, cross or lee-bow after you tack and what

kind of a situation that will put you in. Because of the 'rule' that

is often seized upon about tacking immediately when in dirty air

(which is great advice in most situations) there are a huge amount of

sailors who will tack immediately after realizing that they are in dirty air without (quickly) planning their escape properly, so after their immediate tack, they proceed to do a series of

poorly executed emergency maneuvers (especially in breeze), dropping their mainsheet to be able to

duck, throwing in out-of-control crash tacks into even worse positions etc. all because they didn't take the time to quickly plan out or visualize what exactly bailing out is going to involve and where in the grand scheme of the fleet they will end up having to

sail (maybe they will get to sail in clean air but on a side that has a crippling tactical disadvantage). So if you are going to tack, first crane your neck to see what it will involve and plan your escape route, making sure that you are

psychologically prepared for the boat-handling that will be required

directly after the bailing-out tack. I say 'if' you are going to tack because there are still some other options if sailing to the wrong side looks very bad. Once you have assessed how much

disadvantage (or advantage) bailing out will cause you tactically, you

should always examine the alternative of footing off drastically or even

reaching into clear air. It could be that if you reach through one

boat's dirty air to the clean air downwind but bow even with (that is

abeam of) a boat that was giving you dirty air, you may then be able to

hold that position relative to the lead boats indefinitely in clean air. Although you are one ladder rung down (ladder rung being an arbitrary

measurement), you might be one of the first boats in the group

to get to the shift or the pressure or the current relief etc. that lead

everyone to go left in the first place. Reaching or footing drastically

will obviously lose you ground, but you must compare that with how much

ground you anticipate losing by tacking out and ducking and sailing

away from the tactical advantage. You should also compare the cost of bailing by tacking and the cost of footing off for a lane against the (terrible)

disadvantage of staying put in dirty air. In rare situations it could be that if you tough

it out for 15 seconds in dirty air the whole fleet will tack on a shift (onto port) and you can either immediately

tack into a clear lane if there is one or hold off with your starboard rights for a boatlength or two and then tack into the next available clear lane as it opens up to get back in phase with the shifts.

So the last thing I should be telling sailors going into a big fleet scenario is to

sail in dirty air. In fact I'll say straight out: Don't sail in dirty air! But having said that, when you find yourself starting to eat dirty air quickly think ahead, quickly predict what is about to happen, quickly think through your

options and make calculated decisions (that you can evaluate later). As always if none of your options are any good, take a step back and look at the decision that you made, consciously or unconsciously before that situation that led you to be in the position where all your options were bad. Maybe you could have made different decisions earlier about where to set up on the line. Maybe you could have decided to pull the trigger 5 seconds earlier so that you were not shot out of the front row and so on.

*I just want to back track a bit to the asterisk at the starboard tacker's transom. I said 'if you are able to get a good rounding'. Now that may be a big 'if'. If your buffer boat is not giving you a huge amount of room to duck the starboard boat and if you have to bear off significantly to get behind the starboard tacker's transom it makes it hard to get back up to close hauled without putting yourself in a position where you will be lee bowed by your buffer boat). The solution is a trick that I picked up from the RYA Tactics book, but it is difficult to execute. Rather

than reaching down and calling for room to duck from your buffer boat,

RYA Tactics has you seeing the situation coming early and with room to spare, before the starboard boat is converging perilously with you, you luff up, converting some of your speed to upwind distance, and

then you bear off to get back up to speed and make a nice rounding on the starboard boat's transom. In this way you are still on the same ladder wrung as your buffer boat, because you could think of it like an even rabbit start off the starboard boat's transom, but you are further to windward of your buffer boat so you keep a lane

between yourself and them and you avoid being lee bowed.

Saturday, November 30, 2013

Wednesday, November 20, 2013

Oman Weather and Tactics

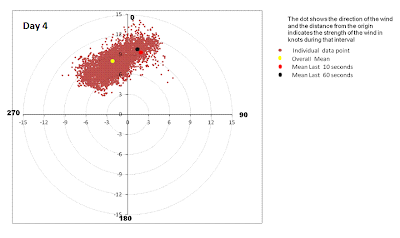

My father is on the way to Oman for the Master Laser Champs and he had some questions about the weather graphs posted on the worlds website, and since he has been reading RYA Tactics but he doesn't use a compass he had some questions about how to pick up on things without a compass. Since this is off-season for many of us, it is also the season for reading up on tactics theory so I figures that I would share my response with the blog followers. So here are some of my thoughts based on the first four days of weather graphs at Oman, which are available here: Day 1, Day 2, Day 3, Day 4 (of the Laser World Championships which run directly before the Masters Laser World Championships for which my father is preparing).

At the bottom left of the weather graphs (click here to go to the page that leads to the weather graphs) there are a few viewing options. Under "Radar

Graphs" on the left there is a circular graph where the distance away from the centre is the percentage of the time that the wind spent at that angle, and the side of the circle indicates the direction that the wind was blowing from. So from that we can tell that the wind rarely shifts more than 10 degrees each way when it is coming from the East South East. On days 2 and 3 the graph is very slightly skewed left, which would indicate that all else being equal (and is probably not) it is more likely that if you went left you would get a left shift to help you get back to the middle of the course than if you went right. So

the strategy on a big course would be at the bottom of the course to head left while the course is square and then to tack back in any time you get knocked with a leftie, then once you are most of the way up the course start working back right any time the wind comes back to neutral or left, only tacking back towards the left when there are relatively bigger (10 degree) righties because they shouldn't last long (the reason that you would work back right would be so as not to get in trouble with the busy layline). That is digging pretty deep for strategy, I think that for a lake sailor the breeze would seem very stable.

Graphs" on the left there is a circular graph where the distance away from the centre is the percentage of the time that the wind spent at that angle, and the side of the circle indicates the direction that the wind was blowing from. So from that we can tell that the wind rarely shifts more than 10 degrees each way when it is coming from the East South East. On days 2 and 3 the graph is very slightly skewed left, which would indicate that all else being equal (and is probably not) it is more likely that if you went left you would get a left shift to help you get back to the middle of the course than if you went right. So

the strategy on a big course would be at the bottom of the course to head left while the course is square and then to tack back in any time you get knocked with a leftie, then once you are most of the way up the course start working back right any time the wind comes back to neutral or left, only tacking back towards the left when there are relatively bigger (10 degree) righties because they shouldn't last long (the reason that you would work back right would be so as not to get in trouble with the busy layline). That is digging pretty deep for strategy, I think that for a lake sailor the breeze would seem very stable.

Day 2 and 3 and also Day 1 have the wind exactly at the

median about 45% of the time,

whereas on Day 4 there is a range of about 10 degrees that the wind stays at for just under 25% of the time, which is the median. Also the wind fairly regularly shifts ten or more additional degrees either way outside of that range. So that is a situation where it would look more like lake sailing. Lots of shifts and not so much of an obvious median. So with the information we have looked at in this graph it seems that the strategy in a Northerly (NNW) would be to be very sensitive to wind shifts and to stay on the lifted tack as the most important part of your strategy, more important than getting to a specific side or other tactical considerations. Looking closely at the graph it looks like having wind from the NNW is slightly more likely than 350 degrees, but I think that the wind is spending more time to the right of 350degrees than to the left of NNW, so if in doubt, I would work my way right (after looking at other graphs that take into account time this proves to be correct for more reasons). The thing is that at the regatta you won't get the info from these graphs until after the races, so it will be interesting to see whether we get a few more Northerlies to see whether the slight right-skew holds. If that is a pattern then you could make a plan based on it, but it is possible that Northerlies are just very random. So we should keep checking in on these graphs to see if we can pick up on any recurring trends. Do you know whether Northerly is an off-shore breeze in Oman?

whereas on Day 4 there is a range of about 10 degrees that the wind stays at for just under 25% of the time, which is the median. Also the wind fairly regularly shifts ten or more additional degrees either way outside of that range. So that is a situation where it would look more like lake sailing. Lots of shifts and not so much of an obvious median. So with the information we have looked at in this graph it seems that the strategy in a Northerly (NNW) would be to be very sensitive to wind shifts and to stay on the lifted tack as the most important part of your strategy, more important than getting to a specific side or other tactical considerations. Looking closely at the graph it looks like having wind from the NNW is slightly more likely than 350 degrees, but I think that the wind is spending more time to the right of 350degrees than to the left of NNW, so if in doubt, I would work my way right (after looking at other graphs that take into account time this proves to be correct for more reasons). The thing is that at the regatta you won't get the info from these graphs until after the races, so it will be interesting to see whether we get a few more Northerlies to see whether the slight right-skew holds. If that is a pattern then you could make a plan based on it, but it is possible that Northerlies are just very random. So we should keep checking in on these graphs to see if we can pick up on any recurring trends. Do you know whether Northerly is an off-shore breeze in Oman?

To be honest I don't know that the bar graph to the right

on the Radar Graphs page is measuring, I think it has to do with wind

strength. But I think we can learn more about wind strength from the

Wind Polar Graph tab.

Wind Polar Graph: On this tab you see pink dots

measuring the wind direction and strength. The further away from the

centre the windier, and you can read the actual wind speeds by following

the curved lines over to an axis (and ignoring the negative signs), so

if you click backwards and forwards between Days 2 and 3 on two browser

tabs, they look like they are different, but if you read the mean wind

speed (yellow dot), in both cases it comes to about 13 knots, they have

just scaled the axies differently between the two tabs. So Days 2 and 3

so far

look like carbon copies of one another in wind speed as well as direction. Day 1 which was a few degrees right of Days 2 and 3 when we looked at it under Radar Graphs has its mean dot also at around 13 knots but there is a bigger spread between lightest and heaviest wind (and if you click back and forth between Days 2 or 3 and Day 1 under Wind Polar Graphs you can see

that the dots are indeed a bit further right on the circle). This could mean that when the wind was a bit further right (Day 1) it was puffier and there were bigger holes/calm spots (after looking at other graphs it turns out that it was actually because of a building trend in the wind). In contrast Days 2 and 3 had blobs of pink dots that were more circular indicating a more random distribution around the mean, less variance in wind strength. With these pretty well symmetrical graphs (Day 1, 2 and 3) you don't have to think too much about relating strength to direction, but on Day 4 the graph is not symmetrical about the centre point of the circular graph. The further right the wind went, the stronger the wind was. That is hugely important, that means that the puffs came more from the right in this case in a northerly (let's see if that happens again another day), so after looking at the Wind Radar graph we thought that

it would be slightly beneficial to go right just because the wind spent slightly more time coming from the right. We can now gather that during these periods when the wind went right it was also stronger, so now the strategy becomes to sail out right whenever there is a lull until you hit a puff which is probably also a right shift (header) at which point you tack on the header and sail back into the middle of the course cashing in your gain from sailing fast in pressure. The trick here is to recognize as you come back into towards the middle when you are no longer in pressure. Puffs are usually pretty dramatic, but lulls often sneak up on you gradually, so you have to be careful to recognize when you are going slower and in this case when you start to get knocked. When you recognize either of these you would tack back right for more pressure. Because this is relatively difficult to realize, I'll offer a couple more cues to pick up on. One would be that the puff might be visible on the water (in this case you would be expecting it on the right). Look for darker water on the right in the distance. Depending on how distracted you are and how much salt water has caked up on your glasses you might not be able to see the shifts early enough. If you see the puff too late it is often not worth going for them because you end up getting there after it is no longer a significant puff, or the direction has gone back to mean. Or you even end up over where the puff was when it is now a lull. That is what we are talking about when we say that someone is "chasing puffs" or someone is "out of phase [with the wind]" in which case they might start taking on lifts instead of headers or tacking on headers that only take them back to the median wind direction. Another more obvious cue to tack back over to the favored side is if you see a group of boats sailing towards you. In this case you have the option to tack and sail in the same direction as them or you can duck or cross them. In this Oman Northerly situation you would want to resist the temptation to use up your slight starboard right of way advantage to cross someone and instead tack with them before you get too close to them so as to to lead them on port towards the next right side shift/puff. If you tack to lead a group of boats towards the favored side with enough distance between you and them you will not be pinned when you finally get to the puff and get knocked and you will have enough leverage (lateral distance along the race course) to gain some noticeable ground on that group. Tacking to lead a group requires you to be shuttling your focus fairly well so that you are aware of the group of boats coming before they are on top of you. Another consideration in these conditions is not to overshoot the right layline because you get so carried away with leading rightward. That being said, if there is good pressure out on the right spending a bit more time on or slightly over the layline in pressure is not the end of the world if the alternative is to be sailing in lighter dirtier air further left on the course.

look like carbon copies of one another in wind speed as well as direction. Day 1 which was a few degrees right of Days 2 and 3 when we looked at it under Radar Graphs has its mean dot also at around 13 knots but there is a bigger spread between lightest and heaviest wind (and if you click back and forth between Days 2 or 3 and Day 1 under Wind Polar Graphs you can see

that the dots are indeed a bit further right on the circle). This could mean that when the wind was a bit further right (Day 1) it was puffier and there were bigger holes/calm spots (after looking at other graphs it turns out that it was actually because of a building trend in the wind). In contrast Days 2 and 3 had blobs of pink dots that were more circular indicating a more random distribution around the mean, less variance in wind strength. With these pretty well symmetrical graphs (Day 1, 2 and 3) you don't have to think too much about relating strength to direction, but on Day 4 the graph is not symmetrical about the centre point of the circular graph. The further right the wind went, the stronger the wind was. That is hugely important, that means that the puffs came more from the right in this case in a northerly (let's see if that happens again another day), so after looking at the Wind Radar graph we thought that

it would be slightly beneficial to go right just because the wind spent slightly more time coming from the right. We can now gather that during these periods when the wind went right it was also stronger, so now the strategy becomes to sail out right whenever there is a lull until you hit a puff which is probably also a right shift (header) at which point you tack on the header and sail back into the middle of the course cashing in your gain from sailing fast in pressure. The trick here is to recognize as you come back into towards the middle when you are no longer in pressure. Puffs are usually pretty dramatic, but lulls often sneak up on you gradually, so you have to be careful to recognize when you are going slower and in this case when you start to get knocked. When you recognize either of these you would tack back right for more pressure. Because this is relatively difficult to realize, I'll offer a couple more cues to pick up on. One would be that the puff might be visible on the water (in this case you would be expecting it on the right). Look for darker water on the right in the distance. Depending on how distracted you are and how much salt water has caked up on your glasses you might not be able to see the shifts early enough. If you see the puff too late it is often not worth going for them because you end up getting there after it is no longer a significant puff, or the direction has gone back to mean. Or you even end up over where the puff was when it is now a lull. That is what we are talking about when we say that someone is "chasing puffs" or someone is "out of phase [with the wind]" in which case they might start taking on lifts instead of headers or tacking on headers that only take them back to the median wind direction. Another more obvious cue to tack back over to the favored side is if you see a group of boats sailing towards you. In this case you have the option to tack and sail in the same direction as them or you can duck or cross them. In this Oman Northerly situation you would want to resist the temptation to use up your slight starboard right of way advantage to cross someone and instead tack with them before you get too close to them so as to to lead them on port towards the next right side shift/puff. If you tack to lead a group of boats towards the favored side with enough distance between you and them you will not be pinned when you finally get to the puff and get knocked and you will have enough leverage (lateral distance along the race course) to gain some noticeable ground on that group. Tacking to lead a group requires you to be shuttling your focus fairly well so that you are aware of the group of boats coming before they are on top of you. Another consideration in these conditions is not to overshoot the right layline because you get so carried away with leading rightward. That being said, if there is good pressure out on the right spending a bit more time on or slightly over the layline in pressure is not the end of the world if the alternative is to be sailing in lighter dirtier air further left on the course.

The main thing that we have not taken into account so far

in looking at the graphs is whether any of the trends that are

happening are related to time. Time is important because with the current information it conceivable that on Day 1, with the data points that spread more between light and heavy

wind, the wind could either have started out heavy and became lighter or, more

likely in a sea breeze environment, the wind could have started out light and

became heavier (with the next graph we find that the latter is correct). If one of

these is the case then our worries about there being big puffs and big

holes are not well-founded, for example it could have been a very

gradual increase in wind without obvious puffs or lulls. So lets check

out a graph that factors in time of day: Click on the Wind Graph tab.

Wind Graph: There is a lot going on in these graphs. As

indicated to the right of the graph the red line is the wind direction

and the blue is the wind strength. The scale for the wind direction is

recorded on the left of the graph and the scale for the wind strength is

recorded on the right of the graph. The peaks and troughs of this line

indicate how drastic the shifts typically are, so on Day 1 we are

seeing mostly 5-10 degree shifts until 18:05 =6:05pm, then things start

getting

a bit more crazy with bigger 15 degree shifts for the next half hour. Interestingly at 18:05 you also see the wind strength start to dip. So this is a familiar situation: the wind dies a bit and starts to shift more dramatically "goes light and shifty" for a half hour. But before you get too carried away with imagining that, you have to read the scale: according to the scale this brief dying trend is only from about 13 knots to about 10 knots, so nothing too crazy. Later on the wind picks back up again and becomes relatively more stable. One thing that will be difficult for a lake sailors is figuring out these longer period shifts. It appears from the graph that many of these shifts are taking as much as 5 minutes to turn one way before coming back the other way. On our lakes we are used to shifts lasting maybe 30 seconds or less, up to a minute or so and we are used to tacking on them immediately so as to cash in on a relatively short course. It is hard to know how many times per minute the measurements for this graph were taken, it could very well be that the measurements were taken over such long periods that the 30 second or less shifts were not picked up. However I imagine that Oman is a big open sea venue and in these venues the shifts often do take a lot longer to pass through their cycles. So as a lake sailor you have to have a lot more patience. Wait two or three times as long as you are used to. When you feel a shift you can think about it: is this a particularly big shift or not? Was it just an apparent wind trick as a result of turning up and down through the waves or from a puff or lull? If I tack on this will I be going the right way in the grand scheme? Then you can tack on the shift after 5 seconds of deliberation (assuming there is no pressure form other boats to make the call more quickly). This is in contrast to lake sailing when a half second means a half boatlength because the course is short and the shifts are quick.

a bit more crazy with bigger 15 degree shifts for the next half hour. Interestingly at 18:05 you also see the wind strength start to dip. So this is a familiar situation: the wind dies a bit and starts to shift more dramatically "goes light and shifty" for a half hour. But before you get too carried away with imagining that, you have to read the scale: according to the scale this brief dying trend is only from about 13 knots to about 10 knots, so nothing too crazy. Later on the wind picks back up again and becomes relatively more stable. One thing that will be difficult for a lake sailors is figuring out these longer period shifts. It appears from the graph that many of these shifts are taking as much as 5 minutes to turn one way before coming back the other way. On our lakes we are used to shifts lasting maybe 30 seconds or less, up to a minute or so and we are used to tacking on them immediately so as to cash in on a relatively short course. It is hard to know how many times per minute the measurements for this graph were taken, it could very well be that the measurements were taken over such long periods that the 30 second or less shifts were not picked up. However I imagine that Oman is a big open sea venue and in these venues the shifts often do take a lot longer to pass through their cycles. So as a lake sailor you have to have a lot more patience. Wait two or three times as long as you are used to. When you feel a shift you can think about it: is this a particularly big shift or not? Was it just an apparent wind trick as a result of turning up and down through the waves or from a puff or lull? If I tack on this will I be going the right way in the grand scheme? Then you can tack on the shift after 5 seconds of deliberation (assuming there is no pressure form other boats to make the call more quickly). This is in contrast to lake sailing when a half second means a half boatlength because the course is short and the shifts are quick.

Anyway getting back to the overall analysis, it looks

like Days 2 and 3 are not quite as identical as it seemed from the other

graphs because whereas Day 2 has the wind slowly and steadily building

through the 3 hours of data, Day 4 has a consistent amount of wind

throughout. In a building breeze it is even more important to get clear

air especially on the downwind so that each new wave of increased

pressure is actually carrying you forward, rather than just getting

lost in the crowd of boats around you. However that also goes for other wind trends. Day 1 also seems to have a building trend, but that lull around 18:20 is interesting. It could be that there were roving lulls (holes) around the race course and it just happened that a lull passed by wherever the weather instruments were over that period. Day 4 on the other hand appears to have some crazy stuff happening. The wind strength was pretty constant with maybe a 2 knot

increase over 3 hours. But directionally there was some interesting stuff. Before getting into the really wierd lines on the graph towards the end of the day, let's look at some of the stuff earlier on. From 11:45 to 12:15, so easily enough time for a leg or two, the wind did a persistent right shift, meaning that you would have had to sail a header into the right of the course in order to sail a lift back into the mark, thereby sailing the inside track of the persistent shift (sailing a shorter radius along the persistently curved track). That would have been a very difficult strategy to decide on however because for an hour before that period the wind seems to be oscillating pretty randomly. Also it turns out that if you had been unlucky at the end of that trend you would have been caught by a 35 degree leftie over 5 minutes leaving you totally screwed on the right of the course unless you had already made it around the mark (at a major event like this they would most likely cancel the race with a shift like that). The fact that that giant leftie could come in and ruine a well thought-out tactic seems pretty disheartening, but it could be seen as encouraging. I know that I often make tactical decisions that I think are sound and then end up getting screwed. In the absence of this graph I could think that my (perfectly sound) tactics are flawed, but here we have, recorded on paper proof that there are situations where essentially correct tactical decisions could get you screwed. This is why we have drop races. But before abandoning hope in the race if something like this came though, there may have been some telltale cues to pick up on in the scenario where this is a race that doesn't get cancelled, cues that would not have saved you, but could have minimized the damages. If you keep shuttling focus between your boat speed, your boat on boat tactics and the overall fleet position, you might have started to notice some boats on the opposite side of the course pointing in a very strange position, or maybe a wind line appeared on the horizon or on the sore line at the left. Maybe a flag or a smoke stack upwind started showing warning signs of a bizzare direction, or maybe it is very last minute and you just notice the boats upwind of you getting the shift. At that point it would be too late to cross the course and get to the left before the shift hits and if you tried to cross over you would have ended up lost in the middle of the course. This is where the principle of 'winning your side' comes in. The group of sailors way out left who are now winning by a lot because of all the distance they have away from you (leverage) are not worth taking into account, but if you can get to the left of the boats on your (right) side of the course as this leftie fills in you will at least be ahead of the boats near you and so you have minimized the damages. You will be behind the people who went left but ahead of the people who wend right and that's how good sailors get consistent results. They don't buy the lottery ticket and go left when the fleet's tacticians go right, they go to the apparently favored side and benefit from it most of the time and minimize the damages the odd time that it doesn't pay.

lost in the crowd of boats around you. However that also goes for other wind trends. Day 1 also seems to have a building trend, but that lull around 18:20 is interesting. It could be that there were roving lulls (holes) around the race course and it just happened that a lull passed by wherever the weather instruments were over that period. Day 4 on the other hand appears to have some crazy stuff happening. The wind strength was pretty constant with maybe a 2 knot

increase over 3 hours. But directionally there was some interesting stuff. Before getting into the really wierd lines on the graph towards the end of the day, let's look at some of the stuff earlier on. From 11:45 to 12:15, so easily enough time for a leg or two, the wind did a persistent right shift, meaning that you would have had to sail a header into the right of the course in order to sail a lift back into the mark, thereby sailing the inside track of the persistent shift (sailing a shorter radius along the persistently curved track). That would have been a very difficult strategy to decide on however because for an hour before that period the wind seems to be oscillating pretty randomly. Also it turns out that if you had been unlucky at the end of that trend you would have been caught by a 35 degree leftie over 5 minutes leaving you totally screwed on the right of the course unless you had already made it around the mark (at a major event like this they would most likely cancel the race with a shift like that). The fact that that giant leftie could come in and ruine a well thought-out tactic seems pretty disheartening, but it could be seen as encouraging. I know that I often make tactical decisions that I think are sound and then end up getting screwed. In the absence of this graph I could think that my (perfectly sound) tactics are flawed, but here we have, recorded on paper proof that there are situations where essentially correct tactical decisions could get you screwed. This is why we have drop races. But before abandoning hope in the race if something like this came though, there may have been some telltale cues to pick up on in the scenario where this is a race that doesn't get cancelled, cues that would not have saved you, but could have minimized the damages. If you keep shuttling focus between your boat speed, your boat on boat tactics and the overall fleet position, you might have started to notice some boats on the opposite side of the course pointing in a very strange position, or maybe a wind line appeared on the horizon or on the sore line at the left. Maybe a flag or a smoke stack upwind started showing warning signs of a bizzare direction, or maybe it is very last minute and you just notice the boats upwind of you getting the shift. At that point it would be too late to cross the course and get to the left before the shift hits and if you tried to cross over you would have ended up lost in the middle of the course. This is where the principle of 'winning your side' comes in. The group of sailors way out left who are now winning by a lot because of all the distance they have away from you (leverage) are not worth taking into account, but if you can get to the left of the boats on your (right) side of the course as this leftie fills in you will at least be ahead of the boats near you and so you have minimized the damages. You will be behind the people who went left but ahead of the people who wend right and that's how good sailors get consistent results. They don't buy the lottery ticket and go left when the fleet's tacticians go right, they go to the apparently favored side and benefit from it most of the time and minimize the damages the odd time that it doesn't pay.

At about 13:15 of Day 4 it looks like there was an insane

direction switch with across the graph but this is not the case, this

is just bad graphing. The compass is a circle, so, for example a 10

degree shift could take you 355 degrees on the compass to 5 degrees.

This is a 10 degree shift, not a 350 degree shift as the graph would

have you believe. So the thin black trend line is incorrect, this is

not a hard right shift, but a slight left shift. So after our half hour

right trend that I just discussed ending at 12:15, there was actually

an hour and a half trend left over 35 degrees from about 335 degrees to

about 10 degrees (remember that 0 degrees aka 360 degrees on a compass

is North). If we look back at the Wind Polar Graph from Day 4 we can

see that

what most likely happened was that at the beginning of racing the wind started to the left and was lighter (than the yellow dot) and throughout the day the wind got slightly windier and went much further right. In general it is not worth looking at the black and red dots because they only represent a couple of data points and because of random variation they could give you all sorts of misleading information. But in this case they happen to be consistent with our theory. The black dot representing the last minute of data was indeed further right and windier than the yellow dot that represents an average from the whole day. The last 10 seconds (red dot) happens to line up with the directional trend by being even further right than the black dot, but ten seconds is such a fleeting moment that I don't read much into that or the fact that it is slightly less windy than the black dot.

what most likely happened was that at the beginning of racing the wind started to the left and was lighter (than the yellow dot) and throughout the day the wind got slightly windier and went much further right. In general it is not worth looking at the black and red dots because they only represent a couple of data points and because of random variation they could give you all sorts of misleading information. But in this case they happen to be consistent with our theory. The black dot representing the last minute of data was indeed further right and windier than the yellow dot that represents an average from the whole day. The last 10 seconds (red dot) happens to line up with the directional trend by being even further right than the black dot, but ten seconds is such a fleeting moment that I don't read much into that or the fact that it is slightly less windy than the black dot.

So ya there is a lot that you could read into the graphs, the perils of asking an engineer about a graph...

Your

other question was about how to pick up on shift directions without a

compass. It is possible that in Oman on one tack you might be pointing

towards a shore. In that case you can take a transit each time you tack

and as you sail on a shoreward tack, keep an idea of where your boat is

pointing relative to any landmarks or buoys on the water. The problem

with this relative to a compass is that each time you tack you have a

new transit that you can't really compare to the last one because you

have sailed up or down the shoreline. With a compass you can compare

headings on one tack and with a bit of mental math (adding or

subtracting your tacking angle) you can compare your heading between

tacks. In the absence of a compass when you are using transits try to

imagine a transit that leads from your centerboard through your mast and

through your bow eye straight forward. Unless there is current, this

should stay constant until you get a shift. In contrast, if you are

hiking hard and you sight through your mast because just because it is

convenient your transit will change as you sail forwards and shifts

could be harder to pick up.

Unfortunately I expect that there will rarely be any

usable transits in Oman, so you have to pick up on other cues. Try to

keep an impression of how the other boats look relative to you and have

an idea of who you can see through the window in your sail and who you

cannot. Then you can reverse this trick and get an idea of whether the

other person can see you through their window or not. I think that

depending on where I am sitting, I can usually cross someone who I can

see through my window, especially if they are far away, and conversely

someone will probably cross me if they can see me through their window.

If you check in regularly with this and other visual cues (am I looking

more straight at that boat's transom or bow or more at the side of

their boat for example) you can get an idea of who is lifted, who is

knocked and who you will or will not be able to cross. That is not to

say that crossing them is important, it is more about figuring out which

ladder rung of the race course you are on. if you can cross someone

you are on a higher ladder rung than them. Instead of crossing a person

it is usually much more important to follow your game plan and that

usually means tack with a boat or set of boats to lead them to the

favoured side of the course regardless of whether you are on a higher or

lower rung than them.

On the other hand if it is an even race course and the game is to tack on the shifts, you can pick up the shifts like this. When it is shifty you will notice that one minute you can cross someone and the other minute they can cross you. Let's start out with another boat on the same ladder rung coming towards you on the opposite tack. If you suddenly realize that they are now able to cross you when they couldn't have before, tack, because you have been knocked and they have been lifted. This also lets you get to the next shift first and lets you cash in on the leverage between you at your next advantage. If, in the other situation, you realize that you are now crossing someone who you wern't before, keep sailing towards them because you are lifted and they are headed and you want to close the gap between you and reduce the leverage so that even if the other person gets another shift later on, the distance between you will be less so they will gain less relative to you what you gained when there was more separation.

Other cues to look for on the race course can be marks of the course: reach marks, the windward mark (leeward mark on the downwind), navigation buoys etc. These cues and the boat-on-boat cues are important to pick up on regardless of whether you have a compass. For example if you did have a compass you might have your compass telling you that you are sailing in consistent breeze, but your windward mark telling you that you are knocked. So after you puzzle that one out... you might realize that in fact you are not getting knocked, you are being set down by the tide/current, so later in the upwind leg, you will actually have to overshoot the layline to get around it. One limitation of the compass is that it tells you your own wind condition, whereas this type of visualizing of the whole fleet can give you information about other parts of the course or about parts of the course yet to come for which you can get prepared early.

On the other hand if it is an even race course and the game is to tack on the shifts, you can pick up the shifts like this. When it is shifty you will notice that one minute you can cross someone and the other minute they can cross you. Let's start out with another boat on the same ladder rung coming towards you on the opposite tack. If you suddenly realize that they are now able to cross you when they couldn't have before, tack, because you have been knocked and they have been lifted. This also lets you get to the next shift first and lets you cash in on the leverage between you at your next advantage. If, in the other situation, you realize that you are now crossing someone who you wern't before, keep sailing towards them because you are lifted and they are headed and you want to close the gap between you and reduce the leverage so that even if the other person gets another shift later on, the distance between you will be less so they will gain less relative to you what you gained when there was more separation.

Other cues to look for on the race course can be marks of the course: reach marks, the windward mark (leeward mark on the downwind), navigation buoys etc. These cues and the boat-on-boat cues are important to pick up on regardless of whether you have a compass. For example if you did have a compass you might have your compass telling you that you are sailing in consistent breeze, but your windward mark telling you that you are knocked. So after you puzzle that one out... you might realize that in fact you are not getting knocked, you are being set down by the tide/current, so later in the upwind leg, you will actually have to overshoot the layline to get around it. One limitation of the compass is that it tells you your own wind condition, whereas this type of visualizing of the whole fleet can give you information about other parts of the course or about parts of the course yet to come for which you can get prepared early.

Before the start the best way to keep and eye on how the

wind is tracking without a compass is to keep an eye on the committee

boat and the pin and go head to wind regularly. Ideally there would be a

transit to take when you go head to wind but that probably won't be the

case. Instead visualize the imaginary line from the committee to the

pin and see how square your boat points to this imaginary line when you

go perfectly head to wind. I find that this is easiest to visualize

this when I am very close to the committee boat or pin (pin is usually

less crowded) and when I stick my hands out either side of my boat in a

line perpendicular to the breeze, a line that would be parallel to the

start line if the start line was square to the current wind direction.

Obviously this process falls apart without a compass if they move the

committee or pin, but if they do that it is usually a recognition by the

race committee that the shifting trend is going to stay, or even a

prediction by the RC that the wind will shift probably based on radio

info from their mark boat way upwind, so it is very valuable

information, maybe the trend will continue... So keeping an eye all the

time on the actions of the race committee and comparing the angle of

your outstretched arms to the angle of the startline can be a nice

substitute for (or addition to) a compass and it can help you get a feel

for the frequency of the shifts, do they come more or less every

minute? 5 minutes? When you are doing this it is also important to

take into consideration that the RC may be skewing the line because of

tactics on the race course: if you must get left to get out of adverse

current , a good RC would purposefully set the committee upwind of the

pin, or committees will often favour the pin when all else is even

because lots of people prefer to start at the committee out of habit and

because committee-end starters have the option to tack out more

easily. So you could be pondering whether any of these things might be

coming in to play when you compare your own measurements to the angle of

the start line.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)